A recent topic of the Write The Docs’ great newsletter was READMEs. It read “As they’re often the first thing people see about a code project, READMEs are pretty important to get right.”. In this post, we’ll share some insights around the READMEs of R packages: why they’re crucial; what they usually contain; how you can best write yours. Let’s dive in! 🏊

Why is a good README key

As mentioned above, the WTD newsletter stated that READMEs are often the first entry point to a project. For a package you could think of other entry points such as the CRAN homepage, but the README remains quite important as seen in the poll below

When I try to become acquainted with a new (to me) #rstats package, I prefer to read ___________

— Jonathan Carroll (@carroll_jono) March 2, 2018

A good README is crucial to recruit users that’ll actually gain something from using your package. As written by noffle in the Art of README,

“your job, when you’re doing it with optimal altruism in mind, isn’t to “sell” people on your work. It’s to let them evaluate what your creation does as objectively as possible, and decide whether it meets their needs or not – not to, say, maximize your downloads or userbase.”

Furthermore, you can recycle the content of your README in other venues (more on how to do that – without copy-pasting – later) like that vignette mentioned in the poll. If you summarize your package in a good one-liner for the top of the README,

> Connect to R-hub, from R

you can re-use it

- as Package Title in DESCRIPTION,

Title: Connect to 'R-hub'

-

in the GitHub repo description,

-

in your introduction at a social event (ok, maybe not).

Other parts of a pitch are good talk fodder, blog post introductions, vignette sections, etc. Therefore, the time you spend pitching your package in the best possible way is a gift that’ll keep on giving, to your users and you.

What is a good README

In the Art of README, noffle includes a checklist; and the rOpenSci dev guide features guidance about the README. Now, what about good READMEs in the wild? In this section, we’ll have a look at a small sample of READMEs.

Sampling READMEs

We shall start by merging the lists of top downloaded and trending CRAN packages one can obtain using pkgsearch.

library("magrittr")

trending <- pkgsearch::cran_trending()

top <- pkgsearch::cran_top_downloaded()

pkglist <- unique(c(trending[["package"]], top[["package"]]))

This is a list of 184 package names, including effectsize, Copula.Markov, leaflet.providers, farver, renv and httptest. Then, again with pkgsearch, we’ll extract their metadata, before keeping only those that have a GitHub README. More arbitrary choices. 😬

meta <- pkgsearch::cran_packages(pkglist)

meta <- meta %>%

dplyr::mutate(URL = strsplit(URL, "\\,")) %>%

tidyr::unnest(URL) %>%

dplyr::filter(stringr::str_detect(URL, "github\\.com")) %>%

dplyr::mutate(URL = stringr::str_remove_all(URL, "\\(.*")) %>%

dplyr::mutate(URL = stringr::str_remove_all(URL, "\\#.*")) %>%

dplyr::mutate(URL = trimws(URL)) %>%

dplyr::select(Package, Title, Date, Version,

URL) %>%

dplyr::mutate(path = urltools::path(URL)) %>%

dplyr::mutate(path = stringr::str_remove(path, "\\/$")) %>%

tidyr::separate(path, sep = "\\/", into = c("owner", "repo"))

str(meta)

## Classes 'tbl_df', 'tbl' and 'data.frame': 122 obs. of 7 variables:

## $ Package: chr "effectsize" "leaflet.providers" "farver" "httptest" ...

## $ Title : chr "Indices of Effect Size and Standardized Parameters" "Leaflet Providers" "High Performance Colour Space Manipulation" "A Test Environment for HTTP Requests" ...

## $ Date : chr NA NA NA NA ...

## $ Version: chr "0.0.1" "1.9.0" "2.0.1" "3.2.2" ...

## $ URL : chr "https://github.com/easystats/effectsize" "https://github.com/rstudio/leaflet.providers" "https://github.com/thomasp85/farver" "https://github.com/nealrichardson/httptest" ...

## $ owner : chr "easystats" "rstudio" "thomasp85" "nealrichardson" ...

## $ repo : chr "effectsize" "leaflet.providers" "farver" "httptest" ...

At this point we have 122 packages with 122 unique GitHub repo URLs, pfiew.

We’ll then extract their preferred README from the GitHub V3 API. Some of them won’t even have one so we’ll lose them from the sample.

gh <- memoise::memoise(ratelimitr::limit_rate(gh::gh,

ratelimitr::rate(1, 1)))

get_readme <- function(owner, repo){

readme <- try(gh("GET /repos/:owner/:repo/readme",

owner = owner, repo = repo),

silent = TRUE)

if(inherits(readme, "try-error")){

return(NULL)

}

lines <- suppressWarnings(

readLines(

readme$download_url

)

)

if (length(lines) == 1){

sub(readme$path, lines,

readme$download_url) -> link

} else {

link <- readme$download_url

}

tibble::tibble(owner = owner,

repo = repo,

readme = list(suppressWarnings(readLines(link))))

}

readmes <- purrr::map2_df(.x = meta$owner, .y = meta$repo,

.f = get_readme)

The readmes data.frame has 117 lines so we lost a few more packages.

Assessing README size

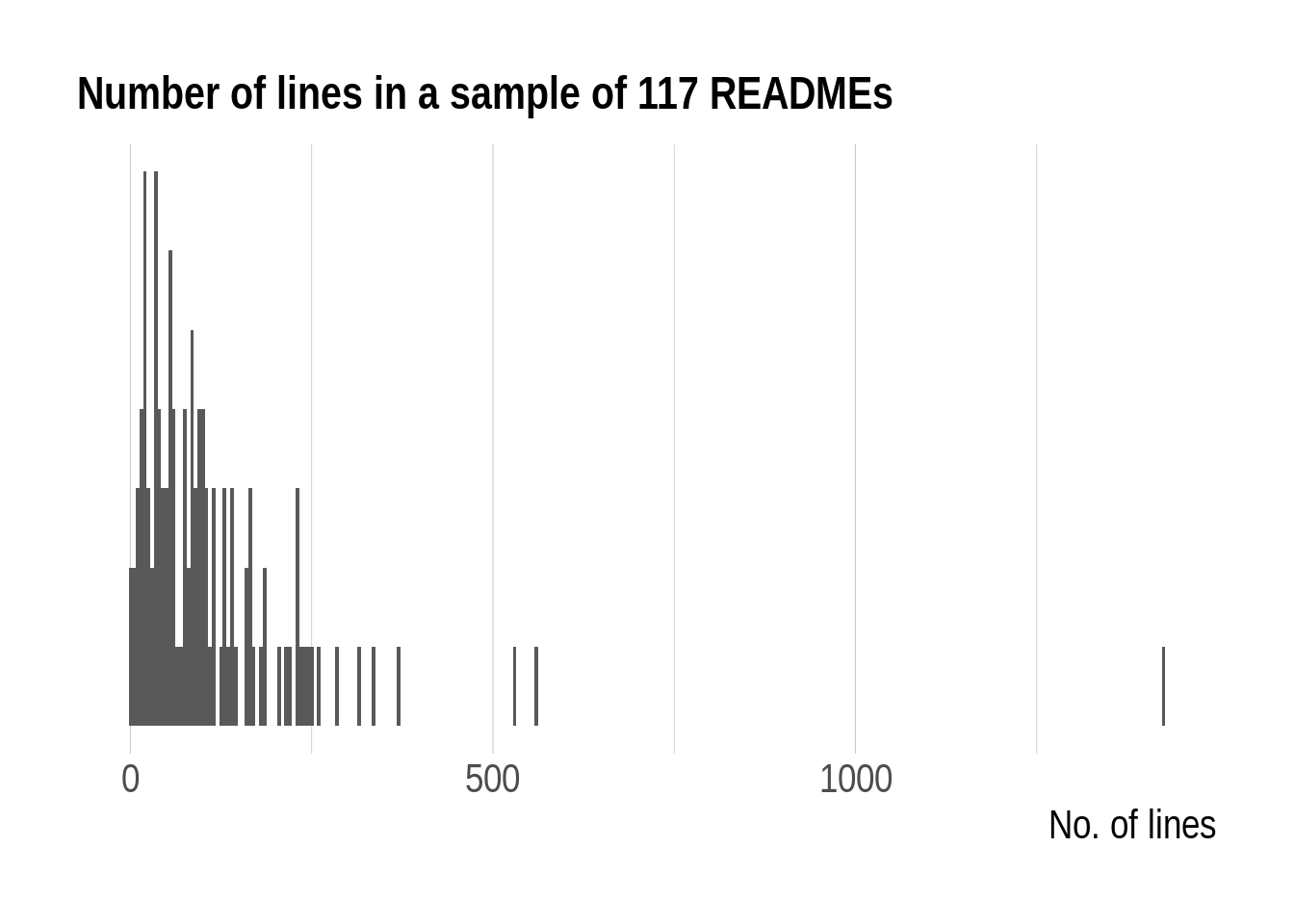

Number of lines

A first metric we’ll extract is the number of lines of the README.

count_lines <- function(readme_lines){

readme_lines %>%

purrr::discard(. == "") %>% # emtpy lines

purrr::discard(stringr::str_detect(., "\\<\\!\\-\\-")) %>% # html comments

length()

}

readmes <- dplyr::group_by(readmes, owner, repo) %>%

dplyr::mutate(lines_no = count_lines(readme[[1]])) %>%

dplyr::ungroup()

How long are usual READMEs? Their number of lines range from 2 to 1426 with a median of 85.

library("ggplot2")

ggplot(readmes) +

geom_histogram(aes(lines_no), binwidth = 5) +

xlab("No. of lines") +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

hrbrthemes::theme_ipsum(base_size = 16,

axis_title_size = 16) +

ggtitle(glue::glue("Number of lines in a sample of {nrow(readmes)} READMEs"))

Dot plot of the number of lines in READMEs

READMEs in our sample most often don’t have more than 200 lines. Now, this metric might indicate how much a potential user needs to take in and how long they need to scroll down but we shall now look into other indicators of size: the number of lines of R code, the number of words outside of code and output.

Other size indicators

To access the numbers we’re after without using too many regular expressions, we shall convert the Markdown content to XML via commonmark and use XPath to parse it.

get_xml <- function(readme_lines){

readme_lines %>%

glue::glue_collapse(sep = "\n") %>%

commonmark::markdown_xml(normalize = TRUE,

hardbreaks = TRUE) %>%

xml2::read_xml() %>%

xml2::xml_ns_strip() -> xml

xml2::xml_replace(xml2::xml_find_all(xml, "//softbreak"),

xml2::read_xml("<text>\n</text>"))

list(xml)

}

readmes <- dplyr::group_by(readmes, owner, repo) %>%

dplyr::mutate(xml_readme = get_xml(readme[[1]])) %>%

dplyr::ungroup()

This is how a single README XML looks like:

readmes$xml_readme[[1]]

## {xml_document}

## <document>

## [1] <heading level="1">\n <text xml:space="preserve">effectsize </text>\n ...

## [2] <paragraph>\n <link destination="https://cran.r-project.org/package=eff ...

## [3] <paragraph>\n <emph>\n <strong>\n <text xml:space="preserve">Si ...

## [4] <paragraph>\n <text xml:space="preserve">The goal of this package is to ...

## [5] <heading level="2">\n <text xml:space="preserve">Installation</text>\n< ...

## [6] <paragraph>\n <text xml:space="preserve">Run the following:</text>\n</p ...

## [7] <code_block info="r" xml:space="preserve">install.packages("devtools")\n ...

## [8] <code_block info="r" xml:space="preserve">library("effectsize")\n</code_ ...

## [9] <heading level="2">\n <text xml:space="preserve">Documentation</text>\n ...

## [10] <paragraph>\n <link destination="https://easystats.github.io/effectsize ...

## [11] <paragraph>\n <text xml:space="preserve">Click on the buttons above to ...

## [12] <list type="bullet" tight="true">\n <item>\n <paragraph>\n <lin ...

## [13] <heading level="1">\n <text xml:space="preserve">Features</text>\n</hea ...

## [14] <paragraph>\n <text xml:space="preserve">This package is focused on ind ...

## [15] <heading level="2">\n <text xml:space="preserve">Effect Size Computatio ...

## [16] <heading level="3">\n <text xml:space="preserve">Basic Indices (Cohen’s ...

## [17] <paragraph>\n <text xml:space="preserve">The package provides functions ...

## [18] <code_block info="r" xml:space="preserve">cohens_d(iris$Sepal.Length, ir ...

## [19] <heading level="3">\n <text xml:space="preserve">ANOVAs (Eta</text>\n ...

## [20] <code_block info="r" xml:space="preserve">model <- aov(Sepal.Length ~ ...

## ...

Let’s count lines of code.

get_code_lines <- function(xml) {

if(is.null(xml)) {

return(NULL)

}

xml2::xml_find_all(xml, "code_block") %>%

purrr::keep(xml2::xml_attr(., "info") == "r") %>%

xml2::xml_text() %>%

length

}

loc <- readmes %>%

dplyr::group_by(repo, owner) %>%

dplyr::summarise(loc = get_code_lines(xml_readme[[1]]))

The number of lines of code of READMEs range from 0 (for 31 READMEs) to 41 with a median of 2. The README with the most lines of code is https://github.com/r-lib/ps#readme.

What about words in text?

get_wordcount <- function(xml, package) {

if(is.null(xml)) {

return(NULL)

}

xml %>%

xml2::xml_find_all("*[not(self::code_block) and not(self::html_block)]") %>%

xml2::xml_text() %>%

glue::glue_collapse(sep = " ") %>%

tibble::tibble(text = .) %>%

tidytext::unnest_tokens(word, text) %>%

nrow()

}

words <- readmes %>%

dplyr::group_by(repo, owner) %>%

dplyr::summarise(wordcount = get_wordcount(xml_readme[[1]]))

The number of words in READMEs range from 13 to 2105 with a median of 278. The READMEs with respectively the most words and least words are https://github.com/jonclayden/RNifti#readme and https://github.com/jvbraun/AlgDesign#readme.

The README size might depend on the package interface size itself, i.e. a package with a single function/dataset probably doesn’t warrant many lines. Beyond a certain interface size or complexity, one might want to make it easier on potential users by breaking up documentation into smaller articles, instead of showing all there is in one page.

Now, a helpful way to still convey information efficiently when there are more than a few things is a good README structure. Besides, a good structure is important for READMEs of all sizes.

Glimpsing at README structure

To assess README structures a bit, we first need to extract headers.

get_headings <- function(xml) {

if(is.null(xml)) {

return(NULL)

}

xml %>%

xml2::xml_find_all("heading") -> headings

list(tibble::tibble(text = xml2::xml_text(headings),

position = seq_along(headings),

level = xml2::xml_attr(headings, "level")))

}

structure <- readmes %>%

dplyr::group_by(repo, owner) %>%

dplyr::mutate(structure = get_headings(xml_readme[[1]])) %>%

dplyr::ungroup()

Here’s the structure of the 42th README.

structure$structure[42][[1]]

## # A tibble: 12 x 3

## text position level

## <chr> <int> <chr>

## 1 Creating Pretty Documents From R Markdown 1 2

## 2 Themes for R Markdown 2 3

## 3 The prettydoc Engine 3 3

## 4 Options and Themes 4 3

## 5 Offline Math Expressions 5 3

## 6 Related Projects 6 3

## 7 Gallery 7 3

## 8 Cayman (demo page) 8 4

## 9 Tactile (demo page) 9 4

## 10 Architect (demo page) 10 4

## 11 Leonids (demo page) 11 4

## 12 HPSTR (demo page) 12 4

We wrote an ugly long and imperfect function to visualize the structure of any of the sampled READMEs, inspired by not ugly and better code in fs.

Click to see the function.

pc <- function(...) {

paste0(..., collapse = "")

}

print_readme_structure <- function(structure){

structure$parent <- NA

for (i in seq_len(nrow(structure))) {

possible_parents <- structure$position[structure$level < structure$level[i]

& structure$position < structure$position[i]]

if (any(possible_parents)) {

structure$parent[i] <- max(possible_parents)

} else {

structure$parent[i] <- NA

}

}

structure$parent[structure$level == min(structure$level)] <- 0

for (i in seq_len(nrow(structure))) {

if (structure$level[i] == 1) {

cat(structure$text[i])

} else {

if(structure$position[i] == max(structure$position[structure$parent==structure$parent[i]])) {

firstchar <- cli:::box_chars()$l

} else {

firstchar <- cli:::box_chars()$j

}

cat(

rep(" ", max(

0,

as.numeric(structure$level[i]) - 1

)),

pc(

firstchar,

pc(rep(

cli:::box_chars()$h,

max(

0,

as.numeric(structure$level[i]) - 1

)

))

), structure$text[i]

)

}

cat("\n")

}

}

In practice,

print_readme_structure(structure$structure[42][[1]])

## └─ Creating Pretty Documents From R Markdown

## ├── Themes for R Markdown

## ├── The prettydoc Engine

## ├── Options and Themes

## ├── Offline Math Expressions

## ├── Related Projects

## └── Gallery

## ├─── Cayman (demo page)

## ├─── Tactile (demo page)

## ├─── Architect (demo page)

## ├─── Leonids (demo page)

## └─── HPSTR (demo page)

print_readme_structure(structure$structure[7][[1]])

## A Teradata Backend for dplyr

## ├─── Koji Makiyama (@hoxo-m)

## ├─ 1 Overview

## ├─ 2 Installation

## ├─ 3 Details

## ├── 3.1 Usage

## ├── 3.2 Translatable functions

## ├─── 3.2.1 lubridate friendly functions

## ├─── 3.2.2 Treat Boolean

## ├─── 3.2.3 to_timestamp()

## └─── 3.2.4 cut()

## └── 3.3 Other useful functions

## └─── 3.3.1 blob_to_string()

## └─ 4 Related work

print_readme_structure(structure$structure[1][[1]])

## effectsize <img src='man/figures/logo.png' align="right" height="139" />

## ├─ Installation

## └─ Documentation

## Features

## ├─ Effect Size Computation

## ├── Basic Indices (Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, Glass’ delta)

## ├── ANOVAs (Eta<sup>2</sup>, Omega<sup>2</sup>, …)

## └── Regression Models

## ├─ Effect Size Interpretation

## ├─ Effect Size Conversion

## └─ Standardization

## └── Data standardization, normalization and rank-transformation

What are the most common headers?

structure %>%

tidyr::unnest(structure) %>%

dplyr::count(text, sort = TRUE) %>%

dplyr::filter(n > 4) %>%

knitr::kable()

| text | n |

|---|---|

| Installation | 85 |

| Usage | 45 |

| Overview | 23 |

| Code of Conduct | 17 |

| License | 15 |

| Example | 10 |

| Cheatsheet | 9 |

| Features | 9 |

| Getting help | 5 |

| Related work | 5 |

This seems to be quite in line with noffle’s checklist (e.g. having installation instructions). Headers related to the background and to examples might have a title specific to the package, in which case they don’t appear in the table above.

The headers are one thing, their order is another one which we won’t analyze in this post. In the Art of README, noffle discusses “cognitive funneling” which might help you choose an order.

How to write a good README

The previous sections aimed at giving an overview of reasons for writing a good README and content of READMEs in the wild, this one should give a few helpful tips.

Tools for writing and re-using content

R Markdown

In noffle’s checklist for a README one item is “Clear, runnable example of usage”. You probably want to go a step further and have “Clear, runnable, executed example of usage” for which using R Markdown is quite handy. Using R Markdown to produce your package README is our number one recommendation.

usethis’ README templates

To create the README, you can use either usethis::use_readme_rmd() (for an R Markdown README) or usethis::use_readme_md() (for a Markdown README). The created README file will include a few sections for you to fill in.

Re-use of Rmd portions in other Rmds

Then, instead of writing everything in one .Rmd and then copying entire sections of it in a vignette, you can re-use Rmd chunks as explained in this blog post by Garrick Aden-Buie presenting an idea by Brodie Gaslam. Compared to that blog post, we recommend keeping re-usable Rmd pieces in man/rmdhunks/ so that they’re available to build vignettes. In the vignettes, use

```{r child='../man/rmdhunks/child.Rmd'}

```

In the README, use

```{r child='man/rmdhunks/child.Rmd'}

```

Re-use of Rmd portions in manual pages

Since roxygen2’s latest release, you can include md/Rmd in manual pages. What a handy thing for, say, your package-level documentation! Refer to roxygen2’s documentation.

In the R files use

#' @includeRmd man/rmdhunks/child.Rmd

Table of contents

If your README is a bit long you might need to add a table of contents at the top, as done for pkgsearch README. In a pkgdown website, the README does not get a table of content in the sidebar, which might be an argument for keeping it small as opposed to articles that do get a table of contents in the sidebar.

Hide clutter in details tags

You can use the details package to hide some content that’d otherwise clutter the README, but that you still want to be available upon click. You can see it in action in reactor README.

How to assess a README

You should write the package README with potential users in mind, who might not understand the use case for your package, who might not know the tool you’re wrapping or porting, etc. It is not easy to change perspectives, though! Having actual external people review your README, or using the audience feedback after say a talk introducing the package, can help a lot here. Ask someone on your corridor or your usual discussion venues (forums, Twitter, etc.).

Conclusion

In this post we discussed the importance of a good package README, mentioned existing guidance, and gave some data-driven clues as to what is a usual README. We also mentioned useful tools to write a good README. For further READing we recommend the Write the Docs’ list of README-related resources as well as this curated list of awesome READMEs. We also welcome your input below… What do you like seeing in a README?